Echoes of a Grand Age: Cleveland’s Vanished Euclid Avenue

Cleveland in the Romantic Age

At one time, Cleveland was the host to more millionaires than any other city in the world, and they all lived on Euclid Avenue, described by travel guides and America's voice Mark Twain as "the most beautiful street in the world." A glimpse reveals cultivated and manicured lawns with sculptures from around the world, quadruple-lined with handsome American elms, and a parade of 400 mansions in every style, some unbelievable in size.

Fans of Downton Abbey (fictionally set between 1910 and 1930) will be astonished to learn that the lifestyle had a direct parallel in those who lived on Cleveland's Euclid Avenue--carriages with full livery and footmen, full live-in staff, and the high and mighty of America. This age of the grand avenue started around 1860 and saw its twilight around 1910 with the age of the automobile, when American cities began to disperse to the suburbs. Quickly, Euclid Avenue saw not only a decline, but a complete destruction of an incredible past.

[Photos were all gathered from online websites, not cited, as well as scans from public domain articles in newspapers]

The full-livery carriage in the entrance of the 40,000 sq.-ft. mansion of Sylvester Everett.

The 50,000 sq.-ft. mansion belonging to Samuel Andrews (an associate of Rockefeller)--it had 33 rooms and required a full-time staff of 100 servants. It was designed to host the Queen of England; several U.S. Presidents visited instead.

Mark Twain called it the most beautiful street in the world, and his view included the avenues of New York, Paris, and St. Petersburg. A quadruple row of American elms lined the street for four miles. The wrought-iron fences were often works of art. Note also all the steps to assist entrance into carriages, as well as the hitching posts.

John D. Rockefeller prepares to embark down the Avenue. He had two mansions on Euclid Avenue, including the Forest Hill estate. His favorite daily activity was the journey down the avenue.

The grandest of the mansions were between 20th and 40th streets and the stretch was known as "Millionaire's Row". It was so protected that the Euclid Avenue streetcar line was diverted around it. The residents all aspired to create the most beautiful setting possible. The Tudor revival Mather Mansion in the center is one of fewer than ten structures remaining today. It briefly hosted the Cleveland Institute of Music before the school moved to University Circle.

The interiors of the homes spared no expense. The home of Jeptha Wade (wife is pictured on the right), founder of the Western Union Telegraph Company, featured rare imported woods and craftsmen who trained in Europe.

A party on the Avenue, c.1901. Some were described to have cakes stretching to the ceiling, and champagne fountain towers of glasses. House concerts brought in the most famous performers of the day, including Enrico Caruso, Amelita Galli-Curci, and Sergei Rachmaninoff.

One of the earliest and largest palaces was built below 9th street. It was quickly demolished and replaced with shops.

The Norton family lived in high style and included the first president of the board of the Cleveland Orchestra, David Z. Norton.

A collection of 19th-c. architectural styles, the picturesque mansions went on for miles, even beyond University Circle.

The Rockefeller family during an afternoon on the Forest Hill Estate in 1881. Rockefeller's golf course was allegedly second to none. He played daily, rain or shine.

Carriages were an incredible sight on the avenue, and this was the Four-in-Hand Club on Millionaire's Row.

It was on the surface very much a man's world at the time--but in fact all the stay-at-home ladies formed clubs and effected incredible social change and brought charities and progressive work to the city. And they dressed fabulously.

The mansions attracted visitors from around the world. The house in the center, the Stager-Beckwith mansion, still stands today: the last 19th-c. Euclid Avenue mansion in existence. Note the sculptures in the front yard. On the left is the Charles Brush Mansion; to the right is the Wade Mansion.

Euclid Avenue was relatively quiet and enjoyed air fresh until industry pushed residents out with pollution. Sunday afternoon rides were popular with residents and spectators.

Residents were proud of the beautiful settings and the mansions to the north side (on the right) that were set back hundreds of feet from the avenue.

A famous tradition was the winter sleigh races--anybody who was anybody on the avenue had to participate in full livery.

The residents were early industrial and oil barons--and before the federal income tax, they lived like European royalty.

"Autumn" by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes: avenue residents competed with each other during trips to Europe with acquisitions of European masters. This painting sat in Samuel Mather's mansion--later the avenue paintings formed the basis of the Cleveland Museum of Art's incredible collections after the homes were demolished.

The Eels mansion had opulent interiors and was host to six U.S. Presidents.

In the 1800s, the street was lit with romantic gas lamps, before avenue resident Charles Brush invented the arc lamp, the earliest form of street lamp in America.

Inventor Charles Brush was a longtime resident of the avenue, witnessing its quick decline towards the end. In his will he specified that his beautiful home be torn down to avoid his beloved home being turned by a new owner into divided boarding houses, as was common even before the Great Depression.

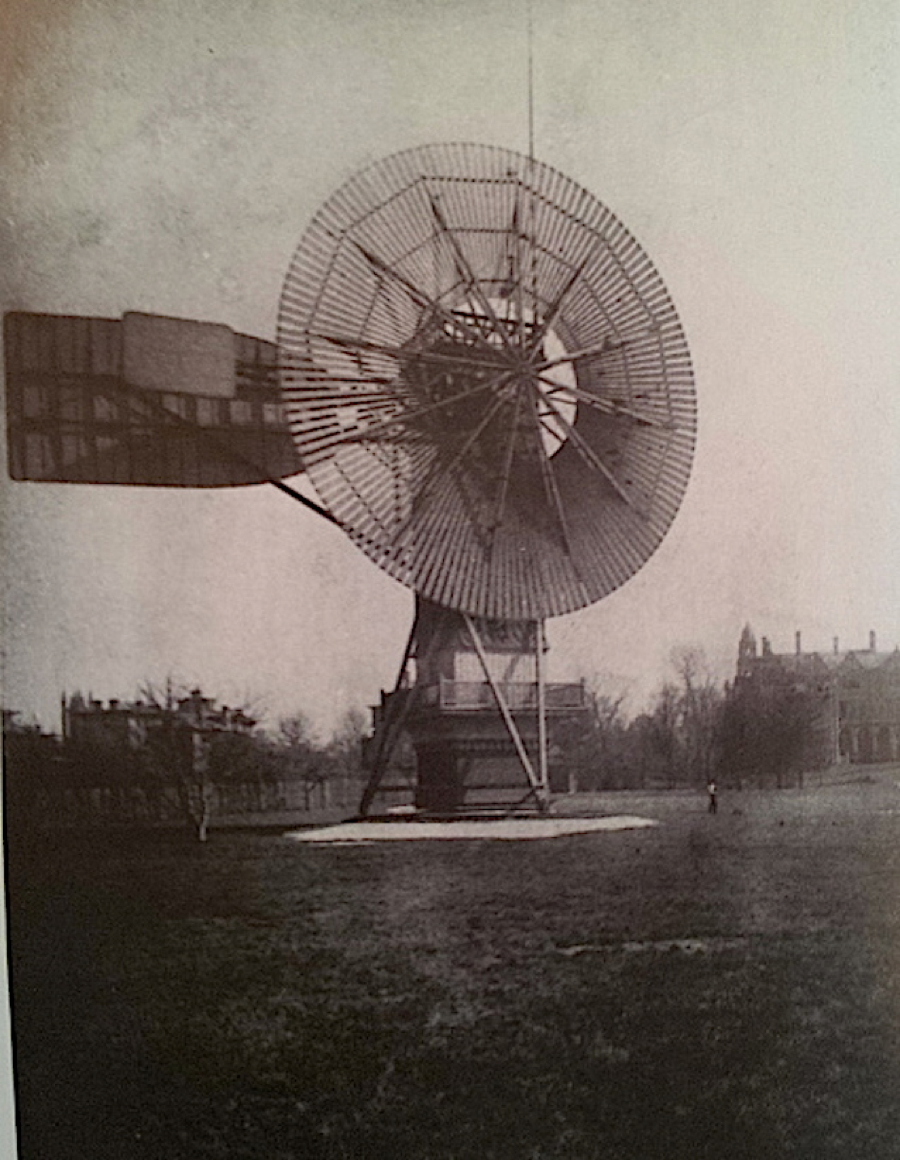

Charles Brush was an inventor whose backyard hosted the world's largest windmill for electricity. Note the tiny size of the human.

The Brush home was outfitted by Louis Comfort Tiffany and the three-story atrium was centered around a Skinner pipe organ.

A wedding party c.1890. I want one of those hats...

Eventually, cars and carriages shared the street, and the character and scale of the avenue began to change.

Any ceremonial parade, such as this one on Washington's birthday in 1889, went down Euclid Avenue.

Fountains and sculptures were a common sight in front lawns--this scene is set in 1870.

The vast home of Sylvester Everett. As with many of the mansions, many U.S. Presidents were frequent guests. This home had a completely sound-proof room for their daughter who was afraid of thunder.

In ornate Richardsonian Romanesque style, the Everett Mansion existed until 1940, when it was finally demolished. An empty parking lot is on the site today.

Interior of the Everett Mansion.

Ella Grant Wilson was a florist and historian for the avenue. She poses here with a sculpture in front of the Everett mansion.

The Mather Mansion was the last to be built, in 1912, and was one of the largest at an estimated 50,000 square feet. It still stands today, largely unchanged--but empty. This home hosted the grandest collections of art and the most incredible musical parties on the third floor ballroom. Pictured are Elizabeth Ring Mather and Samuel Mather. It housed the Cleveland Institute of Music for some years.

The entrance to the Rockefeller Forest Hill Estate: crowds would line the entrance daily to catch a glimpse of the famous man returning home on a daily basis.

Rockefeller playing golf on his Forest Hill courses--dressed like this.

The Forest Hill Estate -- the site is a popular sledding site today in East Cleveland, although the house itself is long gone.

Forest Hill exterior--a strange mix of styles.

Decline and End of the Grandest Era

The end of an era: the Avenue saw its decline with unregulated pushes of commercial construction, taxes, pollution, crime, and the rise of the automobile and subsequent flight to the suburbs. The Andrews mansion sits empty for decades then is demolished in 1923.

Demolition of the Samuel Andrews estate, 1923. By that time, the glory days of the avenue were already over.

Demolition of the Rockefeller Estate at 40th street. To the northwest is the Beckwith mansion.

Demolition of the Hanna mansion to make way for the I-90 Inner Belt Freeway underpass.

A vast void takes the place of the last remaining mansions on Millionaire's Row. They were the last of a unique chapter in American history. Here, the Mather mansion sits displaced from any former context, but housed the Cleveland Institute of Music during these years.